The expression “Small is beautiful” comes from Leopold Kohr; one of his disciples gave it as a title for one of his books, and the phrase became famous.

Kohr’s book is “The breakdown of Nations” (1950). It’s starting to date but remains, precisely, very powerful.

His entire argument can be summarized simply: beyond a certain threshold nothing functions well anymore.

And he explains this to us throughout his book, with examples, political arguments, cultural arguments, philosophical arguments-every subject is involved. Excessive size generates intellectual impoverishment, exacerbated violence (a small war lasts less time and is less violent than a large war), intellectual impoverishment. In a small state tyranny cannot have the intensity of tyranny in a large state. In a small state artists can address responses to our lives as they see fit, while in a large state where everything is segmented and meaning is lost, or where everything is collective and nothing is accessible to the artist, etc, it’s less possible.

We find in all these explanations sources, or at least concomitances, of some of Nassim Taleb’s reflections on city-states. We look at our numerical limits with new eyes: team dynamics that no longer work beyond 9 people, departments or villages that split between 150 and 200 (Dunbar’s number), etc.

So yes, this is the return of localism, proximity, energies understandable and actionable.

And yes, the book is somewhat dated in some reflections, but we should also read it as that of an Austrian humorist and funny man emerging from World War II. Another explanation: if Adolf Hitler had won election in Bavaria (or elsewhere I don’t remember), he would have been the dictator of Bavaria and never that global dictator.

It troubles me in two ways.

The first is Europe. Reading his book, I, a convinced European, find myself doubting “but then…”. Here it comes—we’re at the beginning of Europe, and it seems France is asking for more seats than the Netherlands or Belgium—. His simple proposal: federalism of local communities. To France requesting 22 seats, he says “agreed,” but not 22 centralized seats in Paris, but 2 per region, and each region votes as a region, so potentially not necessarily like France, but perhaps like Lombardy and Flanders.

I rediscover much of the energy found in sociocracy, holacracy, or liquid democracy. It resembles none of these forms exactly, but I find similar energy—an assembly of many local choices generating something that encompasses us all.

We also think about all Illich’s reflections on the interest in proximity (he wrote the preface to the book).

The second is capitalism. It’s fashionable, and very justified it seems to me, to condemn capitalism. He responds similarly: no problem with capitalism itself. The problem is when we exceed a threshold, when something becomes too powerful. In other words, the problem isn’t capitalism but when it falls into the hands of only some. The problem isn’t Amazon itself, but having only one global Amazon. If we had, according to Leopold Kohr, a hundred Amazons across the entire planet-or even thousands—we’d have no problems. It’s precisely because there’s only one, centralized and all-powerful, that everything collapses.

Naturally we think of Mastodon versus Twitter, etc.

The book is also full of little humorous touches—he must have been an exceptional speaker, full of punchlines.

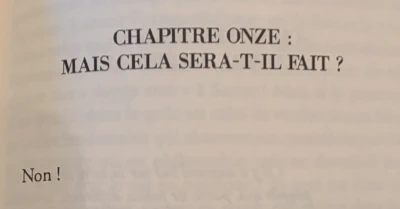

Let us not be too optimistic anyway (who is these days ???), for him we will not resist this folly of grandeur. He gave these recommendations to open chapter 11: “Will it be done?”

Here is the complete chapter 11:

And the 75 years since this book was published have proved him right.

But it’s never too late to try, to change (December 1st the ozone hole was completely healed).